Cookin’ up something Extra Special, adding hops, decorative beer engines, and snow

After bottling beer in Southampton, and labelling beer in Oxford, I can now add brewing beer in Reading to my beery Ale-Wive resume. I’ve always wanted to brew a beer. I mean, can one call oneself a beer writer if one has never made a beer? No, one cannot – I rest my case.

[Note to self: go easy on the third-person point of view]

I’ve drunk copious amounts, had good and bad beers and have learned an awful lot. I’ve spoken with brewers about what and why they brew, but I have not yet made a beer. I’ve read the books and blogs, and magazines, and bottle labels. In theory, I could probably brew a beer, maybe…

Whenever I spoke to brewers, they all told me, like it was something only the actively brewing folk could pass onto the uninitiated non-brewers, “You do know that brewing is 90% cleaning, right?” The way they uttered this was almost like a secret code to deter and sieve through the only partially interested potential beer brewers, in order to keep the secrets of brewing alive amongst the select few.

The husband, always slightly twitchy, knowing how my brain works, was adamant that I shouldn’t home brew. His visions of various brewing paraphernalia arriving at the door, likely kept him up at night, so he insisted I brew with someone who knows what they do.

I’ve brewed my own kombucha before, which means we now share a house with a 3l and a 5l brewing vessel, various sized glass bottles and the odd SCOBY. He, understandably, was right to panic a bit.

So, when I heard the brewing siren call to me with sweet voices, singing to me about the joyous activities of creating a beer, lulling me into naïve enthusiasm, I layered up and left the house to catch a bus at 6:20am.

So far, so good, except it was a rather snowy cold Wednesday morning in March (the first snow day of the whole of 2023… typical) and the bus didn’t turn up. Not only did it not turn up, but it’s tracking GPS signal disappear from the screen, so I can only assume it entered the Bermuda Triangle on its way through rural Oxfordshire somehow and is probably still cruising around undetected and lost. My train, however, was on time (wait a minute…), so I needed to get to the station as soon as possible. Due to the excessive layering of my clothing, all I could manage was a somewhat fast Penguin waddle back home, but waddle I did, and soon I was in a car being driven to the station by the husband. Well, that was the public transport disaster for the day over and done with I thought.

Anyone who has ever walked past or into a brewery know how lush and all-encompassing the smells can be. I’m instantly transported back to my childhood chuggin bottles of Kinderbier. Oh, the sweet malty notes of warmth and security. Interestingly, even though it is called colloquially a KinderBIER (=children’s beer) or MalzBIER (=malt beer), producers of such beverages were not allowed to sell –bier or print the word Bier onto their labels[i], even though the ingredients were suspiciously similar, and it is actually brewed like a beer (it doesn’t undergo fermentation however).

Ladies and gents, I give you the German Reinheitsgebot (= purity decree or often called purity law). Introduced in 1516, it governed German beer manufacture, ensured no adulteration of beer happened, ensured that wheat and rye were only used in bread making, and until the late 1980s, the Reinheitsgebot was actually part of German law. Don’t ever get between a German and their beer and bread. But back to this fateful morning on the outskirts of Reading.

As soon as I walk in, I am welcomed with a hot coffee and an infectious exciting energy: it is International Women’s Collaboration Brew Day (IWCBD), and we are here to collaboratively brew an Extra Special Bitter, also known as a Strong Bitter or ESB, which will be available on keg, cask and in cans[ii]! You can thank me later and like I said, you may kneel in front of my Greatness now!

In case you don’t know, International Women’s Collaboration Brew Day[iii] is the brainchild of British brewer Sophie de Ronde, who founded the day 10 years ago, as a special celebration and to raise awareness of women in the brewing and drinks industry. Check it out if you haven’t yet!

English traditional Bitters, whether Ordinary, Best or Extra Special, occupy a special place in my heart, right next to my other beer love – crisp pilsner.

Take Gravity “The ale formerly known as Brakspear Bitter”  for example – sessionable, restoring, and stimulating. Or, Licher Pilsner – clean, crisp and refreshingly dry.

Yes, you got me there – two very traditional options: the crisp bready Pils to satisfy my German side and the fruity bitterness to pay my British side its dues. European drinker indeed!

Trad Bitters[iv] are sessionable and refreshing, you can easily lose time with friends while drinking pints of the stuff and they have a long history of satisfying customers. And that is what they are brewed for, I might add too. The historian in me likes to romanticise the past and constructed this rose-tinted quint-essential English pub image of punters surrounded by pints of this amber to brown ale. [Soft music playing in the background]

Granted, we still drink like this today, but finding a pub with properly served cask ales can be challenging. I’m not saying that it is impossible, just challenging. Our local, unfortunately, uses 4 out of the 5 available beer engines for mere decoration most of the time, or so it seems. They offer an acceptable pint from the fifth, but it is neither from a local brewery or even the same county, nor is it that exceptional that it should be the only choice.

But Lisa, you can’t blame the pub for this, and should instead look to the drinkers who don’t ask for cask.

I get that, and to some extend it is true, but I don’t think that this is the heart of the problem here. Punters would drink cask ales, if they were on offer. The local CAMRA branch can attest to that, I’m sure. I think it more misunderstanding of English drinking culture, or perhaps a hope to appeal to a more city-like market.

Yes, clean, crisp lagers are fanatic, but putting all on your money on a stout, an ale, 2 lager and 2 premium lager options, just appear a little out of whack, at least for me. Adding to that, that the pub aspires to be more of a gastropub than a local boozer, the food and beer matching options should be in line with said aspiration.

Ok, ok, you got me: I’m just finding it really hard to come to terms with my now rather reduced cask beer options. Having lived in a village with 8 cask ale serving pubs in walking distance, only having access to one which only has 1 choice available, I have indeed become bitter about it.

With my little rant over, let’s get back to the brew house:

The beer we’re collaborating on is a combination of traditionally brewing with modern ingredients. Just some New-World-hops-meets-traditional-grain-bill-magic. Whether or not it should be referred to as an English Bitter is another question, being English would imply only English ingredients where used (English malt, hops and yeast) but then craft brewing has always stuck up its fingers at trad beer as long as it exists, so go figure.

When brewing a traditional bitter, the main goal typically is to achieve balance between English hops, malt and yeast in equal measures. In contrast, a trad Bavarian Hefeweizen, for example will give the yeast the limelight, while a US Westie will allow the hops to shine. A craft bitter or craft hefeweizen may use New Zealand hops and Belgian yeast respectively, instead of the local offerings – But that’s craft, baby!

Trad bitters try to achieve the holy grail of refreshment in a traditional environment– sessionable pints in the local. Craft beer taprooms are about opening the consumer to new aromas, flavours and sensory experiences. Less open fires, worn wood and carpets, more pipes, tiled or painted floors and industrial fittings. Bear this in mind next time you’re in your favourite watering hole: craft beer geeks are far more likely to order 1/3s or 1/2s, while trad beer drinkers tend to opt for a pint. Whether it’s the ABVs or the flavours is debatable, but you get the point.

In all fairness, I’m more than happy sipping on a pint of an Irish dry stout but will only order 1/3 of an American Marshmallow-Orange-Chocolate-Coffee-Tonka Stout.

Back in those good ol’ days, brewers used both terms synonymously in the brewery, as both ales are indeed variations on the theme that is pale ale.

Most pubs would typically offer hopped ales (mild ales, lightly hopped), porters, stouts and more heavily hopped pale ales. Something for every taste and budget so to speak. Those hoppy pale ales were perceived as being more bitter than the Milds (duh! hops!) which appeared to be much sweeter. At this time, pump clips were virtually non-existent, they started to appear in pubs in the 1930s, so punters would ask simply for a pint of beer (today’s porter), a stout, an ale (typically meaning a Mild), and a Bitter beer, Bitter for short.

The name eventually stuck, and nowadays a CAMRA National Pub of the Year isn’t worth its salt if it doesn’t offer a Mild, Bitter and Pale Ale on cask.

But, trying to shuff an ale legend like the English Bitter into a neatly constructed box may not serve the style after all. Yes, back in the olden days, bitters were more bitter, but since the Craft Beer Revolution has turned up the hops to 11, things have changed.

Defining how bitter a beer is, is an odd one as we all perceive bitterness differently. I have a rather high tolerance for bitterness, which allows me to enjoy West Coast IPAs with their bold hop aromas and high bitterness, when others may shy away from them.

But, when some people see me with a pint of Bitter, they tend to screw their nose and mumble something along the lines of “how can you drink this bitter stuff?” while sipping away on an American West Coast IPA…

One way of measuring a beer’s bitterness is by placing a numerical value on it. Humans love to reduce things down to measurable scales, it helps us organise our world better, I guess.

Enter IBU’s Stage right.

IBUs, or International Bitterness Units, are supposed to help a consumer gauge how bitter the beer is. This number measure the bitterness in the beer, but it does not measure the perceived bitterness of the beer. Perception matters people! A beer with an IBU of 60, may not necessarily taste more bitter than a beer with 40 IBUs. It is all about balance. The sum is indeed greater than the parts.

A Pilsner has around 25-45 IBUs, while a Pale Ale sits somewhere between 30 and 50. Interestingly, I really crave the bitterness in a Pilsner, while I like my Pale Ales to offer more of a toasted maltiness with notes of caramel, thereby appearing sweeter.

For reference, IPA’s sit on a range of 50–70 IBUs, and an American lager can be around 5-15 IBUs. Imperial Stouts can sit somewhere between 50- 80 IBU’s, and a Barley wine may clock 100 IBUs. But brewers being brewers, some beers with whopping 1000 IBUs have appear… unspeakably bitter I would imaging, but to be fair, anything over 120 IBUs is probably undetectable for human tastebuds anyway.

It’s also important to note that these numbers are mere a style guide, not law, somewhat akin to what wine drinkers refer to typicity.

Long story short, a beer which indicates a high number of IBU’s can taste well balanced without too much bitterness. Therefore, an English Bitter is indeed a bitter ale, but compared to a West Coast IPA, is comparatively mild. Do IBUs work for consumer? I’m sure some people find them useful. Do I ever refer to them? Before writing this down, I haven’t spent much time pondering those numbers. I know what I like, and I let my palate guide me.

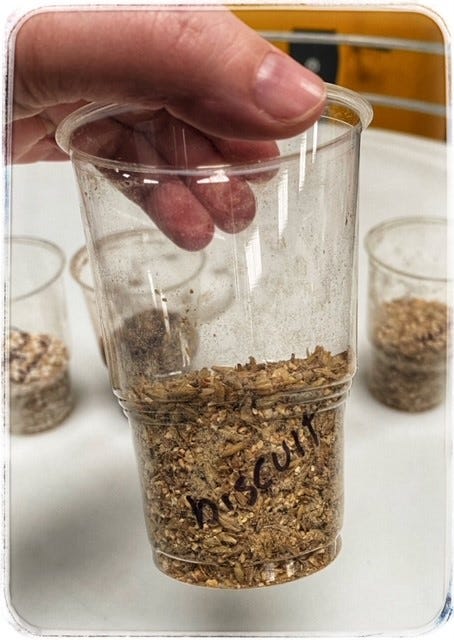

Back in the brewery, observe, take turns spreading various malts onto the mill and watch the grist makes its way into the mash tun from the safety of brewery floor, being made into, the thoughtfully and surprisingly named, mash. We then watch how the mash turns into wort when the spend grains are separated … yadda yadda yadda … and actually taste the liquid. It is hot and sweet and malty and yummy! But it is still a long way from becoming an ESB.

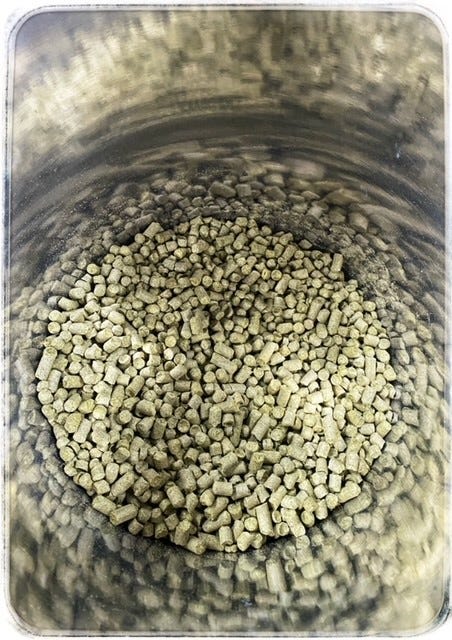

The rest of the day is filled with croissants and pizza, coffee and tea, biscuits and snacks, waiting, networking, and digging out the mash. Have you even taken part in a Collab brew if there is no photo of you shuffling spend grains? We got off lightly though, as we didn’t partake in the various cleaning processes… and yes there is a lot of cleaning involved, and only helped with adding hops at the right points in time. Yes, yours truly added the aroma hop pellets, and man, it smelled like heaven…

Once the wort was locked away securely for fermentation, being an ale, our Modern ESB will take around 3 weeks to ferment, we sampled some beers. We networked and sampled some more beers. It is crucial that, as a newly minted brewer (ahem…), I keep on top of my senses and conduct regular flavour and aroma training, you know.

A few further liquidly samples later, and it was time for a rather jolly Lisa to make her way back home for dinner. Well, remember my trouble getting to the brewery due to lack of smooth-running public transport in the morning? Yeah, my journey home was equally as terrible… signalling problems, previously late running trains and weather conditions … eventually I was in a car being driven home by the husband, with an amazing cooked dinner waiting for me. International Women’s Day indeed!

I am already looking forward to next year! But, as enjoyable and eye-opening the day was, I think I’ll stick to drinking beer, and the husband can sleep well, knowing no brewing equipment will turn up at the house.

A lot of questions have been answered that day, but one new one popped up in my head on the train journey home: why am I so impatient? Three weeks seems a long time to wait…

Might as well get a round in

Cheers! xxx

[i] You typically will see the word Malztrunk (=malt drink) being used instead.

[ii] Uh, a ESB for IWCBD? Isn’t that an old man’s drink and you’re brewing one for International Women’s Day?? Isn’t that a bit stupid? No, no, no! Beer has no gender, and there is nothing like a girly beer or an old man’s drink. Beer is beer. Cider is cider. Wine is wine.

[iii] Unitebrew.org International Women’s Collaboration Brew Day https://unitebrew.org/ [Accessed 13/03/2023]

[iv] Beer Judge certification Program 11. English Bitters https://www.bjcp.org/style/2015/11/british-bitter/ [Accessed 10/03/2023]

Leave a Reply